“Scientists have long appreciated the arts, and even utilized arts in their practice…This does not mean that scientists won’t bring their own perspectives and preconceptions to public art…While none of the associations were likely intended by the artists, I think it’s fun to consider how scientists may perceive and relate to public art.”

Mural of Marie Curie in Warsaw. Painting by Good Looking Studios, photo by Patryk Korzeniecki via Wikimedia Commons

The Association for Public Art asserts that “in a diverse society, art cannot appeal to all people, nor should it be expected to do so.” Professional scientists make up a tiny fraction of society. They are often cast as being dismissive of non-quantitive creative endeavors, and thus less likely to appreciate artistic works.

This may be true of some Ivory Tower silverbacks, but scientists have long appreciated the arts, and even utilized arts in their practice. For example, Galileo is thought to have relied on his musical training to measure time in his experiments.

This does not mean that scientists won’t bring their own perspectives and preconceptions to public art. To explore tropes in public communication, our team was tasked with selecting a piece from the Laramie Mural Project and connecting it to our research. I was surprised how naturally and instinctively we chose our foci, and the number of links we identified. While none of the associations were likely intended by the artists, I think it’s fun to consider how scientists may perceive and relate to public art.

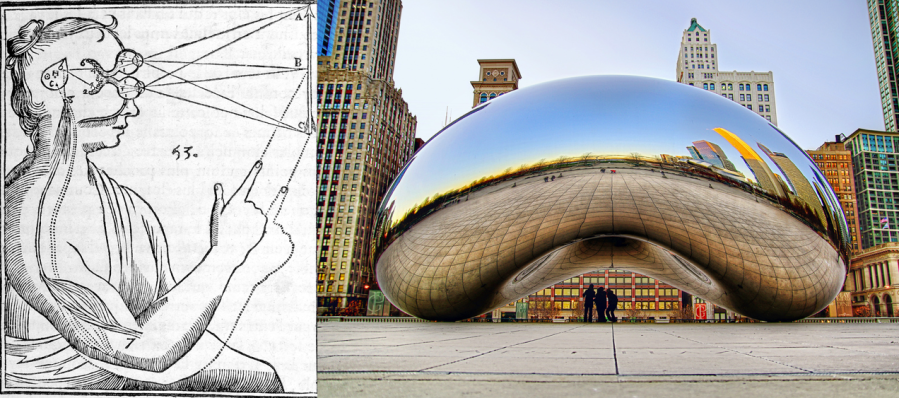

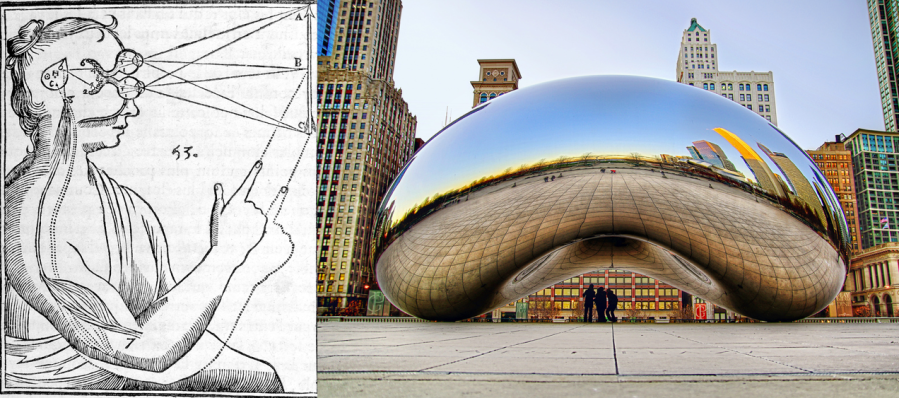

“L’Bean et un traitte…” -Probably not René Descartes

During our discussion, it was quickly apparent how much we appreciated detailed representations of natural systems, and how this led to us breaking art into its component parts. For example, plant ecophysiologist

Daniel Beverly selected

Hollyhock Haven by Travis Ivey, enjoying the enlarged depiction of hollyhocks behind the plants themselves, while the movement of buzzing pollinators is conveyed through detailed shadowing. These interacting components parallels with his research’s perspective of ecosystem health as dynamic process defined by interconnections.

Hollyhock Haven, by Travis Ivey. Located in the City of Laramie parking lot

Soil scientist Chelsea Duball was reminded of how art could illustrate a natural process usually taken for granted, and selected the mosaic “Rainfall to Resources.” The flow of water is represented with handsome, mixed tiling along a gutter’s steel slope. Chelsea’s research centers on soils in wetlands, tracking the path of water into and out of these systems. She was inspired by how the contact between the gutter and the mosaic created an aesthetic highlight for a key but often overlooked process.

Rainfall to Resources. Photo by Chelsea Duball

Art can also work as analogy for one’s science. Astrophysicist

Michelle Mason sees symmetry between Dan Toro’s

Growth and her study on the evolution of galaxies. Michelle described early galaxies as small and far apart–just like the trees on the right side of the mural–while current galaxies are large, complex participants in greater structures (

clusters) like the trees on the left side of the mural.

Growth by Dan Toro

Plant physiologist Heather Sneckman found that art reminded her of the moral motivation of her work. She admires the The Battle of Two Hearts, a statue of the 19th Century Shoshone leader Chief Washakie. Chief Washakie lived in times defined by transformative change and crisis, requiring skill and negotiation from many sides, with resolution coming at great cost. Heather is inspired by Chief Washakie’s adaptation and negotiation through the challenges of his time, and believes that we must emulate those skills as we work to solve ecological, conservation, and humanitarian crises.

Battle of Two Hearts by Dave McGary, photo by Heather Sneckman

Lastly, one piece of art called to mind the act of doing science and the consequence of leaving mysteries unsolved. Amphibian ecologist

Melanie Torres was drawn to Kristina Wiltse’s

Dino Discovery. Melanie studies the enigmatic and terrifying outbreak of

Batrachochotrium dendrobatidis fungus (better known as Bd) in amphibian populations. Along with climate change, habitat change, and pollution, Bd is contributing to global declines of frog populations, which

some scientists claim represents an extinction crisis. Much like paleontologists piecing together a picture of the Mesozoic world, herpetologists are striving to solve the puzzle as to why Bd is moving so quickly, and whether anything can be done to stop it. It is an arduous, complicated process, but of unprecedented importance.

Dino Discovery by Kristina Wiltse

Some of our interpretations may seem tenuous or tangental, but that is to be expected from eyes strained by long hours squinting through microscopes (or binoculars or telescopes or Bayesian simulations). Ultimately, I think we all enjoyed the opportunity to look at the art around us and find a bit of ourselves in it.

Thanks to collaboration and interest from the Laramie Mural Project, the Laramie Public Art Coalition, and the University of Wyoming Press Office, these student interpretations were highlighted in a January 25, 2018 press release issued by UWyo.

Read more about that here.