Post by Caroline L. Rosinski

In spring of 2021 I attended the annual conference of the Western Division of the American Fisheries Society. Held virtually, the conference featured a plenary session about the role of scientists in amplifying science and engaging in advocacy (Pearsons 2021). I, fresh out of a “Science of Science Communication” course, was ready to hear a panel of experts discuss the many benefits of engaging in science communication and using our knowledge of topics to provide input on policy decisions. What I found, instead, was a heated debate between panelists who believed scientists and scientific organizations should advocate for policies their science supports, and those who believed such advocacy would damage credibility, be tainted by biases, and would diminish trust in scientific organizations. Seemingly the only thing these two sides could agree on was that scientists should share their findings with their stakeholders. But the level to which a researcher could interpret those findings or advocate for their application to policy were topics that led to reddening faces and hearty disagreement.

It has been a year since the conference, and I still reflect on this plenary often. I was so surprised by the view that scientists should not engage in advocacy. To me it always seemed like, if our research is being used to inform policy decisions, surely we would be well-suited to advocating for the decision those data support. And perhaps this is a point of distinction – advocating for policies directly related to our research, versus using our authority as scientists to exert opinions on policies unrelated to the work we do. I can certainly understand the latter being problematic and leading to possible distrust in scientific entities. However, I certainly interpreted the anti-advocacy panelists in this plenary as being against advocacy even for those subjects in which they are trained and may hold the most knowledge.

They gave the example of a fisheries professional who does research on river fish populations advocating for or against a dam removal on that river. To me, that fisheries professional is likely the most well-equipped to advocate on behalf of the future of fish populations, and likely their data would support one policy or the other. This seems like a case where advocacy would be acceptable, but some of the panelists disagreed, saying that fisheries professional should only present the facts, and leave interpretation and policy decisions to others.

This semester, in Applied Principles of Science Communication, we read literature pertaining to this exact topic. Kotcher et al (2017) published on the impacts on credibility for scientists engaging in advocacy. Kotcher et al. (2017) cautioned that there was an effect on credibility when the advocacy pertained to a hot-button topic like climate change, however on most topics, people’s perceptions of a scientist’s credibility didn’t change when the scientist engaged in advocacy. I was gratified that the main takeaway of this work was that scientists can engage in advocacy if it is done thoughtfully.

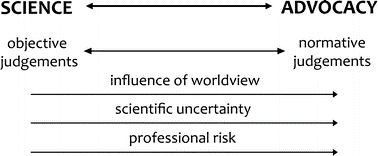

This need to be thoughtful about the extent to which a scientist chooses to engage in advocacy is echoed in Donner’s (2014) essay describing the science-advocacy continuum. Donner (2014) used psychology and communications research to describe a range from purely scientific communications, defined by use of only objective judgements, to communications closer to advocacy that incorporate normative judgements. Donner says a scientist can evaluate where on this continuum they choose to fall but, critically, this must be a conscious decision that considers possible biases to prevent any possible “covert” advocacy (Donner 2014). In the end, Donner (2014) encourages scientists to consider three factors when deciding their place on the science-advocacy continuum – choosing the position that is right for you based on your personality and worldview, considering the organization you represent and how they will be impacted by your decision, and questioning your strengths and motivations to make sure you understand your biases and the extent of your communication abilities.

I wonder if the panelists at that memorable plenary were just at different ends of the science – advocacy continuum and unwilling to acknowledge that this may be a matter of individual choice. Research suggests scientists can engage in advocacy if it’s done thoughtfully and it’s up to the individual to evaluate their values, and those of the institution they represent, to decide whether advocacy is appropriate. I, for one, believe advocating for the policies my data support is likely to increase the chance my data can have a positive impact on management and the future of the fisheries I study.

Caroline Rosinski is a master’s student at the University of Wyoming researching fisheries ecology.

references:

Donner, S.D. 2014. Finding your place on the science – advocacy continuum: an editorial essay. Climatic Change, 124:1-8.

Kotcher, J.E., T.A. Myers, E.K. Vraga, N. Stenhouse, and E.W. Maibach, 2017. Does engagement in advocacy hurt the credibility of scientists? Results from a randomized national survey experiment. Environmental Communication, 11(3): 415-429.

Pearsons, T. 2021. The role of scientists in amplifying science, credibility, and advocacy: A perspective about the plenary. Tributary: Western Division of the American Fisheries Society 45(2).