Post by Shayne Dodge

People tackle reading and assimilating scientific papers in different ways. Some may skim through the sections they find most important, such as the abstract, results, and discussion. Others may read and or re-read each line, trying to squirrel away every nut of information. No matter the technique, the difficulty of understanding seems to increase as the theoretical degree increases—at least for me. While generally, I can readily understand what I read, I have to be able to see the principle used in a practical manner or manipulate it to really be familiar with its innerworkings. So, when I’m reading a paper, I’m looking for ways I can incorporate the information into something I’m familiar with (Dong, Jong, and King 2020).

Recently, when researching the intersection of scicomm and impact-identities, I came across what I thought was one of those more theoretical or at least ideological papers (Risien and Storksdieck 2018). The article was about how over the course of their careers, scientists cultivate a professional identity that corresponds to their research. It notes that, in some circles a person’s professional identity is considered separate from their personal identity—something like the argument of can you separate the scientist from the science. It goes on to describe how a scientist’s research and professional identity inform their impact on society, and how professional and personal identities are somewhat inherently overlapping since they are two parts of the same person. It argues that the single multifaceted identity may be more relatable to, and have greater impacts on, the intersection of science and society.

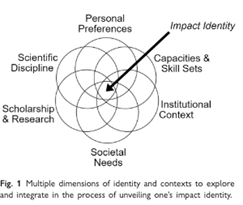

In this article, Risien and Storksdieck (2018) give scientists a process for developing an impact identity that matches their identity as individuals and as scientists. They explaine how this identity can be used to establish a legacy with regard to their work and how its broader impacts relate to society. They describe how the funding landscape of today requires grant seeking scientists to incorporate how their research will be delivered to, and meaningful for, non-scientist members of society. The authors also describe how the broader impacts sections of each grant need not be stand-alone projects, but may be consecutive pieces that form an overarching societal impact project—one’s impact legacy. They narrate the path two scientists chose to accomplish this lifetime broader impacts goal. Finally, the authors describe how a person’s impact identity can be found at the Venn-diagram-center of their individual, and scientific identity, such as personal preferences, scientific discipline, and societal needs, to name a few (Fig. 1).

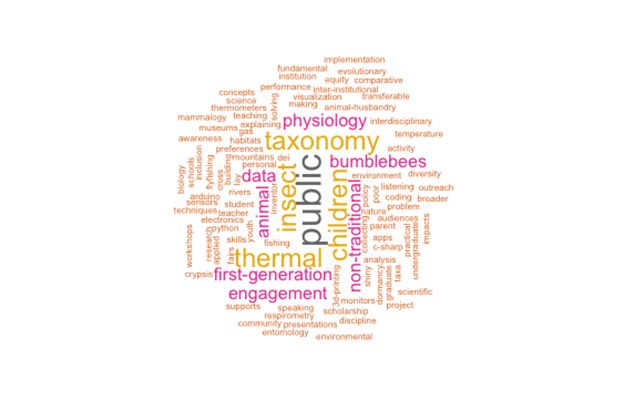

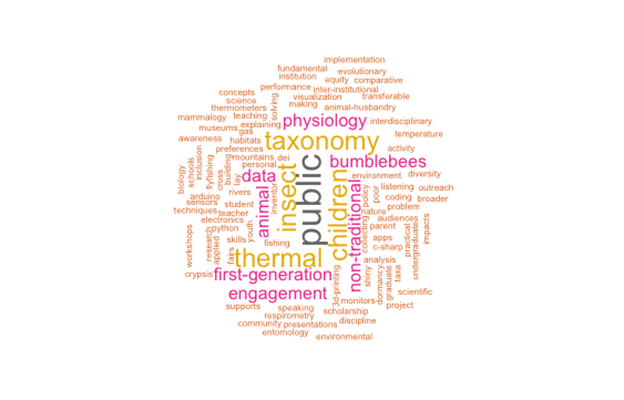

After reading this paper I understood the importance of developing an impact identity and how it could be used to inform how my science may impact society, but even though they explained each dimension of this intersecting impact identity, I was still unsure about how to practically implement the information for myself. Then I had it, as someone who often spends time converting research findings into visual, graphical representations I realized that I could create a Venn diagram analog to help me understand what my impact identity would look like—a word cloud. It was a practical way to incorporate the theory of an impact identity, with a bit of math, to visualize what the center of figure 1 would mean for me. Here’s what I got…

The beauty of this approach is that a word cloud is much like the Venn diagram where the center and some of the largest words around it are equivalent to the Venn’s center, and to attain the cloud I simply filled in information about myself (in word form) for each dimension listed in the paper—personal preferences, scientific discipline, societal needs, etc.—and ranked them by frequency of use, simulating the overlap of the Venn diagram. Those with the largest font are the most frequently used (most overlapping).

This is likely only one of many ways to apply the principles laid out in the article, but I found it somewhat helpful and thought others may too. To accompany this bit of writing, I have written an example of exactly how I was able to make the word cloud. It’s intended for those already using the R language, but who may never have made such a visualization. The code is open source so feel free to share widely and or copy-paste for your own version.

Shayne Dodge is a PhD candidate in the Department of Zoology and Physiology and Program in Ecology and Evolution at the University of Wyoming.

references

Dong, Anmei, Morris Siu-Yung Jong, and Ronnel B. King. 2020. “How Does Prior Knowledge Influence Learning Engagement? The Mediating Roles of Cognitive Load and Help-Seeking.” Frontiers in Psychology 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.591203.

Risien, Julie, and Martin Storksdieck. 2018. “Unveiling Impact Identities: A Path for Connecting Science and Society.” Integrative and Comparative Biology 58 (1): 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icy011.